Food gardeners are an important part of any local food system. In Achieving Sustainability through Local Food Systems in the United States (PDF) (2013), agricultural economists Dale Johnson and James Hanson, Ph.D. state: “By far the greatest, but often overlooked, local food source in the United States is gardening.”

About 35% of Maryland households are doing some type of food gardening and have lots of important questions: What’s this worm eating my kale? How do I improve my soil and test it for lead? How do I start a school garden? Where can I take a vegetable gardening class?

Since 2009 many residents and communities have received science-based food gardening answers and help from Grow It Eat It (GIEI)– one of the six major sub-programs of the University of Maryland Extension (UME) Master Gardener Program that teaches and promotes home, school, and community food gardening. This article serves to introduce this amazing program and some of its successes. I plan to write a second article later this year on some of the exciting 2023 GIEI projects from around the state.

What is GIEI?

Grow It Eat It was developed late in 2008 by UME staff, faculty, and volunteers in response to the Great Recession. Many people were already interested in trying their hand at food gardening as a way to eat more fresh produce and connect with nature. The economic collapse forced folks to find ways to reduce household expenses.

The main GIEI objective has been to increase local food production by combining the power of grassroots education and technical assistance delivered by field faculty and Master Gardeners, with UME’s digital gardening resources. Master Gardeners (MGs) have taught hundreds of classes, developed demonstration gardens, and helped thousands of individuals and groups start food gardens and learn and use best practices. Residents can learn about GIEI classes and events by visiting their local Extension web pages and connecting on social media. MGs also help residents solve food gardening problems at Ask a MG Plant Clinics around the state. The Home and Garden Information Center (HGIC) supports GIEI by training MGs, creating and maintaining digital resources, and answering food gardening questions through the Ask Extension service.

GIEI intersects and collaborates with other MG sub-programs– Bay-Wise Landscaping, Ask a MG Plant Clinic, Composting, and Pollinators– and with UME’s nutrition, natural resources, youth development, and urban ag programs. This helps the program address four of the five Strategic Initiatives guiding the College of Ag & Natural Resources.

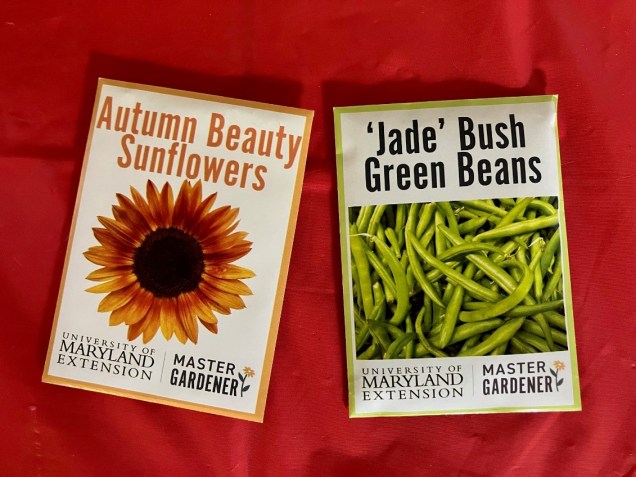

As the faculty lead, I have loved every minute spent working with UME faculty, staff, and volunteers to shape, improve and expand the program. Master Gardener Coordinators and Volunteers decide how to best shape GIEI to meet local needs. The State MG Office organizes regular GIEI statewide planning/sharing meetings and continuing education classes, and provides seeds, teaching, and marketing materials. MGs responded to the pandemic by moving GIEI classes online. GIEI projects and activities steadily increased in 2021 and 2022 and should surpass pre-COVID levels in 2023.